There was a flurry of recent discussion around the Biden-Harris proposal to tax unrealized capital gains, probably best summarized by this “special edition” of the (always excellent) “Best of Econtwitter” substack.

Being a graduate student with nothing better to do, I started by reading the various flurries of commentary on the proposal produced by the twitterati and blogger community, kept clicking hyperlinks, and woke up two weeks later having read much more of the “optimal tax” literature than my advisor would have advised was sensible for someone who is not a tax policy researcher.

What better way to to sink those costs even lower into the ground recoup those sunk costs than to write-up my opinionated and semi-informed takeaways?

The starting point for my confusion was reading two different review papers, both published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, and only published two years apart. One is Gregory Mankiw, Matthew Weinzeirl, and Danny Yagan’s 2009 “Optimal Taxation in Theory and Practice”. The other is Peter Diamond and Emmanuel Saez’s 2011 “The Case for a Progressive Tax: From Basic Research to Policy Recommendations.”

The first paper lays out “eight general lessons” from optimal tax theory, one of which is “capital income ought to be untaxed, at least in expectation.”

The second paper has “three basic policy recommendations from basic research,” one of which is that “capital income should be taxed.”

So, the conclusion you/I/we the reader should have is that….

….

[your guess is as good as mine]

Now, to be fair to the (extremely accomplished) researchers involved, the 2011 paper explicitly acknowledges its disagreement with the 2009 paper — they weren’t just talking past each other. However, as a reader, I was left with more confusions than conclusions.

After having read around a bit more, doubts still proliferate over deductions, but I do have four (tentative) takeaways:

Optimal tax results provide (weak) directional guidance only

Existing cross-country variation in capital taxes (probably) do not significantly affect cross-country growth patterns

“Admin” costs are more important than “fundamental” costs

I would vote to lower capital taxes, but whether or not capital taxes are lowered is of second-order importance

One note of clarification: by “capital taxes” I am referring to any sort of tax on the capital stock or on capital income flows. Wealth taxes, corporate income taxes, property taxes, and individual capital gains taxes are all variations on the theme that is capital taxes.

Now, expanding on each of the four points in turn…

Optimal tax results provide (weak) directional guidance only

The classic papers which argue against taxing capital income are Atkinson and Stiglitz 1976, Judd 1985, and Chamley 1986 (the latter two are often grouped together as “Chamley-Judd”).

The intuition for the result across all of the papers is broadly similar: taxing capital income makes future consumption more expensive than current consumption, and increasingly so with time. Conversely, taxing labor income (or consumption directly) taxes consumption in each period at an equal rate. Relative to an undistorted initial state, there is no reason we should make future consumption relatively more expensive, so capital should not be taxed. Furthermore, by making future consumption more expensive, we will deter investment, preventing the economy from growing as much as it otherwise would.

Many papers since have built on their frameworks and also found that capital taxes should be zero, or even negative (providing a subsidy to capital income).

The logic here is powerful and simple; powerful and simple enough that completely dismissing it would be foolhardy. However, many a simple and powerful economic intuition looks mangled after confronting the jagged rocks of reality (I’m looking at you minimum wage).

For starters, Straub and Werning 2020 show that even in Chamley and Judd’s own model environments, their results are not strictly true. Secondly, under a variety of different assumptions than the original models, optimal capital taxes are positive.

And the assumptions needed to get positive capital taxes are not outlandish, they are eminently innocuous: for example, if people are uncertain about their future income, if people are constrained in their ability to borrow, if people care about accumulating wealth independently of the ability to spend it on consumption, if people who can earn more also like to save more, if people start out with different amounts of wealth, if people systematically have different returns on capital, or if labor income can sometimes be disguised as capital income. And if you put lots of these different frictions together in one unholy soup, you may find that the “optimal savings tax is mostly positive and progressive.”1

Now, I believe “death by a thousand paper links” was not one of Aristotle’s four types of argument for a reason — a zealous zero capital tax advocate could fire back with an equally long list of assumptions and papers which argue against taxing capital. But in this case, a war of “it takes a model to beat a model” strikes me as counterproductive.

The problem is not just that models oftentimes rely on unrealistic assumptions; rather, the problem is that there are multifarious “forces” out there in the world which make capital taxes good and forces which make capital taxes bad. Writing down models helps us clarify which forces push in which direction, but in my opinion, they struggle to capture the balance of forces in a compelling manner.

It is precisely because of the “choose your own adventureassumptions” nature of the game that seasoned economists who have spent years reading these papers can come down on complete opposite sides of the issue — as Mankiw, Weinzeirl, and Yagan do versus Diamond and Saez.

In 2010, the Mirrlees Review was a 2000+ page report which “brought together experts to identify the characteristics of a good tax system for any open developed economy in the 21st century.” Peter Diamond — the same Diamond from the aforementioned Diamond and Saez paper — co-wrote a chapter with James Banks “The Base for Direct Taxation,” which over the course of 100 pages carefully argues for why capital income should be part of the tax base.

Robert Hall — one of the pre-eminent economists of the last 50 or so years, who notably came up with (alongside Alvin Rabushka) a flat consumption tax proposal that many Eastern European countries adopted in the wake of Soviet collapse — was one of the commentators on the chapter. One line from his commentary stood out to me: “My reading of the Banks–Diamond chapter does not convince me that lowering of the British tax on capital income would be an obvious mistake.”

A hedged double negative expressing fundamental uncertainty is where I am also left from reading this literature!

Existing cross-country variation in capital taxes (probably) do not significantly affect cross-country growth patterns

When theory leaves you stuck at a crossroads with signs pointing in conflicting directions, where does one turn? To the Elysian fields of empirics and endogeneity concerns of course.

There are many studies of individual instances where capital taxes changed that examine the short-term dynamics of savings and investment, but I think a more fruitful starting point is to zoom out and look at cross-country and historical patterns: if taxing capital at higher rates deters investment and growth in a significant fashion, you would like to think that pattern shows up in simple analyses.

From the papers I’ve seen, however, no such clear and evident relationship exists.

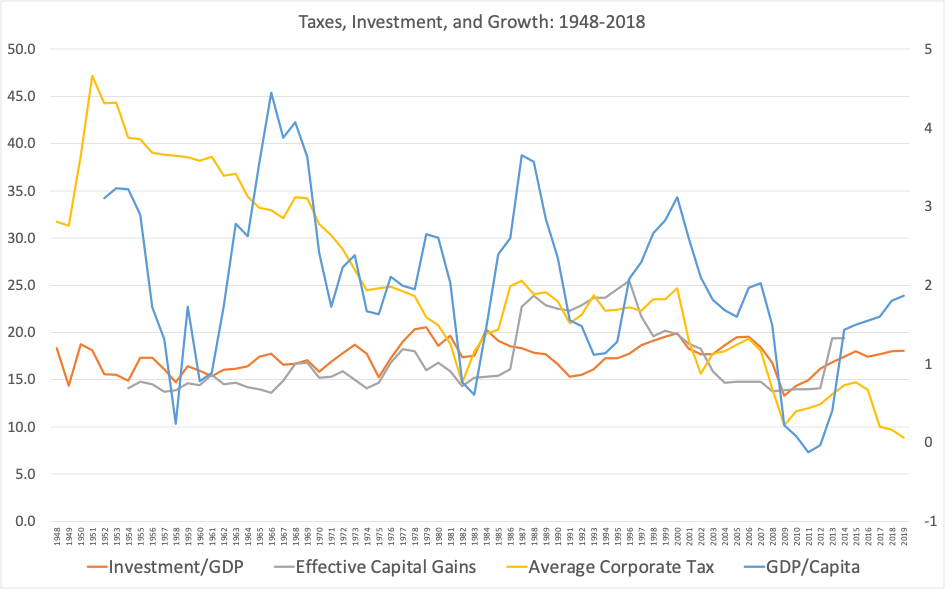

Looking at just the US, Hungerford 2012 finds that “reduction in the top tax rates has had little association with saving, investment, or productivity growth.” Hungerford is looking at all taxes on solely top earners income — things are somewhat more ambiguous for capital taxes writ large. Below I have plotted the average effective tax rate for capital gains, average effective tax rate for corporate income2, aggregate investment/GDP, and a 5-year moving average of GDP/capita growth (on the right y-axis for readability):

Eyeball econometrics says there is no clear relationship here — corporate taxes were much higher in the post-war (1948-70) period, but investment was healthy, and GDP/capita growth was (on average) higher than it has been since. The correlation between GDP/capita and both corporate and capital gains tax rates is positive, same for the correlation between investment and capital gains tax rates.

That being said, there is a -0.28 correlation between the investment rate and the corporate tax rate, driven by the ~1985-2000 period where average corporate taxes rose and investment was relatively muted. One might expect this to lead to a negative relationship between corporate tax rates and subsequent GDP/capita growth, but the correlation between the corporate rate and average GDP/capita growth over the next five years is also positive. If such a relationship does exist, it is more subtle than this aggregate data can capture.

There are some anecdotal instances where changing capital taxes seemed to have large growth effects — Aghion and Roulet 2013 mention the example of Sweden. In 1991, Sweden dropped its top marginal capital income tax rate from 72% to 30%, and annual growth increased by 1-2pp in the following 20 years. However, the Swedish reform also saw a 31pp drop in top marginal labor income tax rates, so it is hard to know how much of the growth effect to attribute to the capital tax change (or other exogenous factors).

What do the results from formal econometric investigations show? I certainly have not been able to canvas the entire literature, but from what I have seen, while some papers find a negative relationship between capital taxes and growth, more papers find negligible or insignificant growth effects, and some papers even find that labor taxes are more harmful to growth than capital taxes. If “human capital” is the resource that is most important to accumulate, it would make sense that labor income taxes have more adverse growth effect than capital taxes. Additionally, the incentive to innovate is increasing in the size of the market, and labor taxes may do more to limit the size of the market than capital taxes.

Perhaps most comprehensively of the papers just linked, ten Kate and Milionis 2019 look at 77 countries, including all of the OECD and some developing countries, over the period 1965 to 2014. They find that "in many specifications, the association between capital taxation and growth rates is in fact positive and in the remaining ones it is not statistically different from zero."

None of the studies just mentioned are able to isolate any sort of exogenous variation in capital income taxes. They are ridden with all sorts of issues that prevent their estimates from being causal. So they are far from definitive evidence. But I would argue that being too hesitant to take anything from “correlational” analyses is its own pitfall. It could not be the case, but if variation in capital taxes has large effects on growth, I would have expected the relationship to be a bit more consistently detectable.

The more careful micro-studies out there do provide convincing evidence of a relationship between capital tax rates and, at the least, investment. To cherry-pick two particularly persuasive recent examples, 1) Moon 2022 looks at a change in capital gains taxes that affected a subset of South Korean firms and shows that (on a five-year horizon) those who faced the tax cut increased investment by 2% for every 1% decrease in their tax rate 2) as reviewed by Chodorow-Reich, Zidar, and Zwick 2024, across multiple ways of analyzing the data, the Trump administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) did boost corporate investment. The authors’ central estimate3 is that in the short-term, investment increased 4% for every 1% decrease in tax rates.

These effects on investment are sizable, but for the TCJA, the implied aggregate effects remain underwhelming.4 Using a model, the authors predict that the TCJA increased long-run GDP by 0.9% . That is the level of GDP, not its growth rate. And that is a mere ~9-19% of the GDP boost the Council of Economic Advisers forecasted the tax reform would have. Furthermore, the tax cuts don’t come close to “paying for themselves” — average tax revenue (over each of the next ten years) is 0.63% of GDP lower.5

I am on board with the idea that the TCJA-based (positive) estimate of the GDP growth effect should be trusted more than the cross-country analyses already discussed. I am also prepared to believe that “very high” — say, significantly above 50% — marginal tax rates on capital have more deleterious effects on growth. Yet, considering all of this evidence synoptically, I see little reason to think, relative to the current level of tax rates, there is a massive “free lunch” in this vicinity, as Bob Lucas once described cutting capital taxes.

“Admin” costs are more important than “fundamental” costs

Given skepticism about the effects of capital taxes on growth, on what basis should we decide whether to tax capital more or less?

I think it’s useful to (somewhat arbitrarily) divide up the effects of different taxes into what I’ll call “admin costs” and “fundamental costs”.6 By “fundamental costs” I mean to refer to the classic primary margin of behavior which each tax (allegedly) distorts. For capital taxes, fundamental costs are changes in investment (and how those changes impact growth). For labor income taxes, fundamental costs are changes in labor supply (and ditto).

Admin costs are the residual — all the other ways in which taxes alter behavior. This is a broad concept. Considering realization-based capital gains taxes alone, examples would include 1) the “lock-in” effect where people are overly incentivized to hold on to winners to avoid paying capital gains 2) the incentives for firms to use profits to pay out dividends versus buyback shares if dividends are taxed differently 3) all the time and energy people spend figuring out how to offset capital gains with losses — including the friends we make tax advisors we hire along the way 4) how much time and resources the IRS has to spend to collect capital gains tax and 5) any hijinks involving shifting income across states/countries to avoid paying taxes.

Corporate taxes, wealth taxes, and unrealized capital gains taxes come with their own corresponding admin costs, as do labor income and consumption taxes.

As far as I’m aware, we lack compelling estimates of these all-inclusive admin costs. We do, however, have plenty of evidence that admin costs abound. And as Brülhart et al. 2022 summarize, “a number of studies have suggested” that the response of overall income to taxation “is largely driven by exclusions and deductions from income, rather than real savings or labor supply behavior.”

Given the finicky and myriad ways these admin costs show up, it is hard to say with confidence which types of taxes look better or worse from the admin cost centric-perspective. But my high-level view is that capital is more mobile than labor and that the capital-rich can afford to engage in more avoidance behavior than the labor income rich. Taking admin costs seriously therefore pushes against taxing capital and towards “simpler” forms of taxation like labor incomes or consumption.

Back in 1990, Joel Slemrod framed this debate as one between “optimal taxation” and “optimal tax systems.” A theory of “optimal tax systems” is one that treats admin costs as a first-order concern. I agree with Slemrod that “differences in the ease of administering various taxes have been and will continue to be a critical determinant of appropriate tax policy.”

I would vote to lower capital taxes, but whether or not capital taxes are lowered is of second-order importance

Personally speaking, I believe in two things: 1) we should have a highly re-distributive welfare state, since well-being is strongly diminishing in wealth and most variation in wealth is due to factors outside of one’s control and 2) creating the conditions for sustained growth in aggregate wealth is very important.

Those statements in conjunction are a stapes of a skeleton of a fully-fleshed out theory of justice — maybe better characterized as a minimal theory of what types of injustice to avoid.

But in light of the preceding discussion, taking those two tenets seriously points to a few conclusions. For starters, there is little evidence that taxing capital around existing levels threatens (2). Without being too political, I would go so far as to say that deciding who one is going to vote for on the basis of how their capital tax policy is going to affect growth is unfounded.7

Taxing capital undeniably helps goal (1). Yet, I also think there is little reason to believe that achieving (1) requires high-taxes on capital. Even if taxes on consumption and/or labor income are less progressive than capital income taxes, as long as the proceeds are spent in a sufficiently progressive manner, the state can succeed in its re-distributional goals.

So, with all of that in mind, why do I say I would vote for lower capital taxes? One main prong of the argument is the (open to change!) belief that admin costs are higher for capital taxes. Martin Feldstein penned a good short report and longer paper which walk through many of the ways a capital tax could be distortionary aside from the traditional savings margin. Two examples are 1) that taxing corporate profits “drives capital out of the corporate sector and into other activities, particularly into foreign investment and real estate”, and 2) that preferentially taxing debt encourages companies to rely on debt more than equity, making “firms more vulnerable to adverse business cycle conditions.” I don’t share Feldstein’s strong aversion to taxing capital, but I am inclined to believe there are more of these sorts of issue with taxing capital than consumption or other sources of income.

The other prong is the (weak) directional guidance I take away from the optimal policy literature. My impression is that in general, even in papers which do find capital taxes are optimal, the resulting “optimal” capital tax rate is not “that” high — where “that” high could be anywhere in the 10-40% range.

For example, the “unholy soup” paper I mentioned earlier is Ferey, Lockwood, and Tabinsky 2024 “Sufficient Statistics for Nonlinear Tax Systems with General Across-Income Heterogeneity,” which just came out in the AER. In their calibration, they explicitly put in multiple forces which push in favor of a capital tax, while omitting forces that push the other way, like lower social than private discount rates or effects of capital taxes on innovation.8 Across a few different ways of specifying things, they get that marginal capital tax rates for higher incomes should be somewhere in the 15-35% range.9

One factor that could push optimal capital tax rates up relative to their model is believing that the US should be more re-distributive than it currently is, since their model takes existing levels of re-distribution as appropriate. But again, that additional redistribution could also be achieved by altering the way the government spends.

This is inevitably quite subjective, but since my sense is the balance of forces in their model are more tilted towards capital taxes than the actual balance of forces out there “in reality”; and since the model doesn’t capture differences in “admin” costs across capital and income taxes; I would lean towards the lower end of their estimates as a guide for policy. Which implies (slightly) cutting existing US top capital gains and corporate income tax rates.10

Ergo, I would vote for lower capital taxes and more progressive spending. But if capital taxes are the only politically viable means of achieving sufficient redistribution, I’m all in favor of modestly raising capital taxes. And if someone wants to raise capital taxes while doing lots of other good things, I’m going to focus on the other matters.

Conclusion

The main takeaway I have come to is following: the extant theoretical and empirical literature does not support the idea that mildly increasing or decreasing capital taxes from current levels matters much for growth or welfare. If someone does believe to the contrary, the burden of proof is on them.

Radical, I know.

My academic compulsion to “cover all my bases” does require me to make the following caveats, however.

Firstly, none of my points here are about the right overall level of taxation. It may be that the US (or the world) would be better off with overall lower or higher levels of taxation — I am not taking a stand on that issue here.

Secondly, in the best of econ twitter newsletter referenced at the very beginning, the (anonymous) author writes that “the platonic ideal is: tax unimproved land and negative externalities alone and forget about everything else if possible.” I am very sympathetic to that idea. My points here are merely about taxing capital more or less relative to the current status quo.

Finally, in a perfect world, universally high capital taxes on exorbitantly high capital incomes seem like a no-brainer to me. If everywhere in the world taxed $1B+ capital wealth at very high marginal rates I seriously doubt that would affect innovation — people will want to get as rich as they can either way. But in a world where a single country can typically only act unilaterally, the arms-race incentives to attract the capital and entrepreneurship of the mega-rich is a material factor.

And, as always, if any readers of these half-baked thoughts can convince me that I’m wrong — please do so.

The paper just linked is Ferey, Lockwood, and Tabinsky 2024 “Sufficient Statistics for Nonlinear Tax Systems with General Across-Income Heterogeneity.” I will discuss this paper a bit more later, but I want to note this paper was very helpful for organizing many of the links in the preceding paragraph.

Using FRED’s tax receipts on corporate income divided by corporate profits before tax.

No aggregate effects are estimated in the South Korea paper since it is a very small subset of firms which saw a change in tax liabilities.

In contrast, in the narrative identification approach of Mertens and Ravn 2012 1pp labor income tax cuts have larger growth effects than 1pp corporate tax cuts (1.8pp vs. 0.6pp boost to gdp/capita), but corporate tax cuts lead to no loss in tax revenue, giving them a larger (undefined) multiplier of output gain/revenue loss.

In Martin Feldstein’s 1999 “Tax Avoidance and the Deadweight Loss of Income Tax” he shows that “tax avoidance” behavior and actual labor supply responses equally cause efficiency losses, so the elasticity of taxable income with respect to taxes summarizes the deadweight loss. My point here is consistent with Feldstein insofar as I am not saying that “admin” costs should be weighted more than fundamental costs; rather, I am saying that admin costs explain more of the variance of the elasticity of taxable income than fundamental costs do. I would also note that I believe “admin” costs is even broader than Feldstein’s “avoidance” behaviors, since something like “lock-in” behavior is part of admin costs, but wouldn’t fall under all ways of measuring avoidance behaviors.

If you want to decide who to vote for based on how it will affect your own income, more power to you, but that is a different conversation.

In the model of Aghion, Akcigit, and Fernandez-Villaverde, the model of Cozzi 2018, and the model of Gross and Klein the welfare effects of the innovation channel are far greater in magnitude than the any of the effects included in the Ferey et al. paper.

This is coming from Figure 4 in the paper.

In Figure 4 in the paper, US marginal capital tax rates are below 15%, but that is because the authors say that property taxes are a tax on renters, not owners, thus setting the tax on all property wealth to 0%, and then including that 0% tax rate as part of the average total capital tax rate. Current US federal top marginal tax rates on capital gains and corporations are 20% and 21% respectively [corporate tax rates are even higher if you include state taxes].

Note that, because capital markets are global, we should not expect a strong correlation between personal taxes on capital and GDP per capita, growth rates, or investment. Corporate income taxes have a stronger effect, because they're levied based on where you invest, whereas personal taxes are levied based on where you live, regardless of where you invest.

Private property is a government service, so one should expect to pay more if one owns more. Wealth taxes have always been problematic, so the usual approach was to tax income generated by that wealth and the gains when realized. This worked moderately well. We saw a boom in growth and innovation back when marginal income tax rates were up around 90%. The modern way of incrementally liquidating companies didn't work at those tax rates, but disinvestment makes perfect sense with modern rates.

Unfortunately, the general growth in liquidity makes it possible to spend unrealized gains all too easily, so the income-wealth correlation doesn't work as it once did. With low interest rates, borrowing against unrealized gains is cheaper than paying capital gains taxes, and with the government pumping money to the wealthy and guaranteeing market performance as it has for the last four or so decades, it's a safe game to play.

Most of what is considered capital these days has nothing to do with investment in the production of goods and services. It's all casino chips. I would like to encourage capital formation in the traditional sense, but current policies don't really work. Real capital formation is much more dependent on government efforts than anything in the private financial sector as we've seen with SpaceX, Tesla, Apple and Google. I doubt that taxing "capital" would have as much of a negative economic impact as traditional theory suggests.