I began writing this post the morning of Wednesday November 6th 2024 — the morning after the US election, where Donald Trump won a reasonably close yet nonetheless resounding victory over Kamala Harris. Why did more than half of the US (voting) populace reject the Biden administration and vote for someone as manifestly unpopular as Trump?

The leading scapegoat seems to be inflation. People were upset about the economy under Biden; people did not trust Kamala to handle the economy well, and the discontent with the economy was more than anything else discontent with inflation. Exit polls (in the US) are notoriously unreliable, but when something looks this much like a duck and quacks this much like a duck, the logical conclusion is…

The natural follow-up question for an out-of-touch, economist-in-training, swamp-resident (swampman?) like myself is “okay, but why do people dislike inflation so much? Shouldn’t wages catch up with prices relatively quickly and living standards remain more or less unchanged? Didn’t Paul Krugman tell us that “most workers have in fact seen wage increases outpacing inflation?”

Well, turns out, if you are so bold as to close FRED for a second and ask people, 81% of people believe that prices increase faster than wages during inflationary times, and 73% of people believe their purchasing power decreases.

But are they right? That is, during the inflation that occurred under the Biden presidency, did the median American worker’s wages keep up with the rate of price increases or not? Surely that is a simple question economists should be easily able to answer?

There has been a fair amount of discourse on this topic throughout the last few years, and the last couple of days since the election have seen Econ twitter flooded with takes: Arin Dube, alongside Jeremy Horpedahl, continues to defend the thesis that real wages “really have risen strongly for the working class in America”; Jason Furman and Ernie Tedeschi both say it’s complicated; Andres Drenik and a team of co-authors have a new paper finding that inflation reduced welfare for the median worker by $5000; and Noah Smith goes so far as to say that “in 2021 and 2022, Americans’ real wages suffered their biggest drop in postwar history”

What’s going on here???

A blooming, buzzing confusion, that’s what. The macroeconomists are at it again, if you will.

I myself have been extremely confused about this issue, and after having spent the bulk of my post-election haze trying to decipher things, I can now report in high spirits that I am only somewhat confused.

Here is where I think things stand:

Inflation did make the median voter poorer during Biden's term.

In no part of the income distribution did wages grow faster while Biden was President than they did 2012-2020.

This is true in the raw data, and even more stark after compositional adjustment.

In particular, the change in median incomes was well below its 2012-20 run-rate.

But, the change in median wages is not what matters; it is the median change in wages that does. And this metric was even weaker under Biden: lower than any period in the last 30 years other than the Great Recession.

People do not feel wages, they feel total income. And median growth in total income — post taxes and transfers — was not just historically low: it collapsed and was deeply negative from 2021 onwards.

Much of this decline is due to timing of pandemic stimulus and even less the “fault of Biden” than other things.

After detailing each of those points in turn, I will explain this figure, which shows how methodological adjustments take you from confusion about why voters hated inflation to surprise that voter’s did not backlash even more:1

Before getting into it, point (2) above is worth spelling out, since I have repeatedly managed to get tongue-tied (keyboard-crossed?) about it while writing this post. The change in median wages represents how wages grew for workers who started 2021 in the middle of the income distribution. The median change in wages, in Matt Bruenig’s helpful phrasing, is “the percent change in wages that is right in the middle of all percent changes in wages.”

To see why the median change in wages is the relevant object for thinking about the election, imagine a world where you had 3 different people: person A with an income of $4, person B with an income of $5, and person C with an income of $10. If four years later person A is now only making $1, person B is making $6, and person C is also making $6, the median income has increased! But if there were an election, the median worker — who is also the median voter2 — did not have a good last four years, financially speaking. Hence why the median change in income is the object of interest.

So, if you are only interested in the takeaways that I believe are most electorally explanatory, skip ahead to the subheadings for point (2) and (3).

Terminological note: I will use “while Biden was in office,” “under Biden,” and “during the inflationary period” interchangeably. That is not to blame Biden, but merely to help orient this analysis around voter sentiment.

Clearing the air: Why don’t we just know?

I mentioned to one of my (micro!) economist friends that I was writing this post and he was incredulous that it was deserving of a post. Shouldn’t we just know, unambiguously, what happened to real wages and incomes over the last few years?

The short answer is twofold: 1) if the question we want to answer is “did inflation during the Biden administration make voters poorer,” there is no single metric which is obviously the “right” way to answer that question. 2) we don’t have access to linked-individual Census tax-data, which would allows us to track the full evolution of within-household income over the last few years.

For the pedants like myself, the footnote at the end of this sentence explains more of what I mean about both points.3 For the non-pedants, the bottom-line is that there is no gold-standard ground-truth here, and instead we need to triangulate a conclusion from multiple different (sometimes confusingly conflicting!) sources.

Point 1: no part of the income distribution outperformed their 2012-2020 trends

First off, I am not going to try and figure out what happened to average wages under Biden. The issue with average wages is that in 2020, low wage workers were disproportionately fired, dramatically pushing up average hourly earnings. Therefore, the change in average earnings from the start of Biden’s tenure onwards is artificially depressed by the high January 2021 denominator.

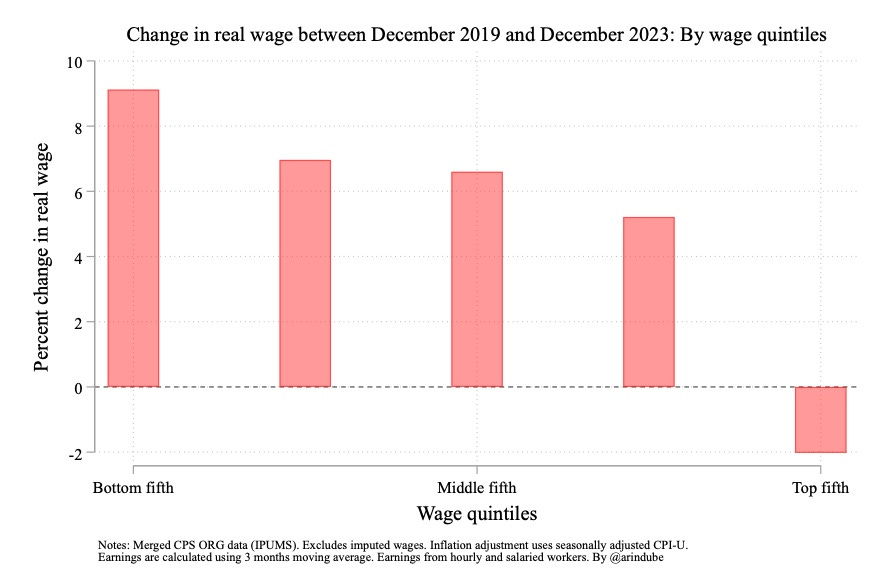

Looking at median wages — or any percentile wage — is somewhat afflicted by the same issues, but less so than the average wage. Using the same data cleaning as Autor, Dube, and McGrew on Current Population Survey (CPS) data, here is what growth in real hourly wages look like, by quintile, comparing Biden’s presidency, Trump’s, and Obama’s second term:4

In this data, while Biden was in office, real hourly wage growth was strong for the lowest income quintile, solid for the middle three income quintiles, and very poor for the highest income quintile. However, aside from the lowest income quintile, while healthy in absolute terms, real hourly wage growth was clearly slower during Biden’s tenure than the four years prior.

In order to see if Covid may still be distorting the data, I plotted separate bars for Trump’s full term and Trump’s term up through February 2020. The discrepancies are not massive, but there is a consistent pattern of the data including Covid looking stronger than the pre-Covid data. Some of that is a “true” effect stemming from low 2020 inflation pushing up real wages, but some of it is likely due to compositional issues still infecting the data.

An alternative measure of real wage growth comes from Ernie Tedeschi, former chief economist on the Council of Economic Advisers (under Biden). Tedeschi’s measure uses the same CPS data we just looked at, but has three important differences: 1) He compositionally adjusts the data so that the sex, age, race, education, industry, and occupation composition of the workforce circa 2023 is “held fixed” when looking at data further back in time.5 2) He includes time-dummies to adjust for residual spikiness in Covid-wages that is not already accounted for by his weighting scheme 3) He looks at weekly earnings rather than hourly earnings.

In Tedeschi’s data, here is cumulative growth in 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile real wages, by President, dating back to Reagan’s first-term:6

Low-income wage growth still looks historically healthy, but is now distinctly weaker than it was during either Obama’s second term or Trump. Meanwhile, annualized real median wage growth is negative — and the lowest of any Presidential term other than Obama’s GFC-ridden first — on this cut of the data.

Having tinkered around with the data a bit, the difference between the results just presented (Tedeschi approach) and the chart one before (Autor, Dube, and McGrew approach) seems to be roughly 2/3 due to using weekly vs. hourly earnings, 1/3 due to the compositional adjustments and time-dummies. Average weekly hours worked (among the employed) declined for the first couple years of the Biden administration, causing a divergence between weekly and hourly earnings. Dube argues we shouldn’t have expected weekly earnings to grow at their 2015-19 trend since 2015-19 was boosted by the labor market reaching full employment, but weekly hours weren’t actually increasing from 2015-19. The period hours increased most was 2009-2012 (Obama’s first term), and as the Tedeschi-based bar chart shows, that boost from hours worked was not enough to offset the declines in real (hourly) wages caused by the Great Recession.

One other piece of evidence we have on median earnings comes from the CPS “annual social and economic supplement” (CPS ASEC), which differs from the regular CPS as follows: the regular CPS is a monthly survey where workers report average weekly or hourly earnings; the CPS ASEC is an annual survey which takes place every March and asks respondents to reports total earnings in the year prior (so the March 2024 survey asks about 2023 calendar-year earnings).

In my opinion, weekly earnings are more relevant than hourly earnings for understanding voter psychology, and likewise, annual earnings are more relevant than weekly earnings: it is annual earnings that determines the overall state of your finances.

Below, I plot growth in real median household pre-tax income, and male and female earnings — again by President. The distinctions to be aware of here are that 1) income includes non-wage forms of income, such as social security income and the earned income tax credit, but does not include Covid stimulus checks; 2) earnings are solely wage income, and are for all workers, not just full-time workers, and 3) this data uses the CPI as its deflator rather than the PCE. The nice thing about these variables is that none of them show an artificial bump in 2020.7

Here we see a story fairly consistent with Tedeschi’s numbers: for male workers, real median earnings fell from 2020 to 2023. For female workers, real median earnings grew slower than all but one Presidency since 1968. When you add in other sources of income, the median income household did experience real income growth, but drastically less income growth than they experienced during the prior eight years.

The data in that chart only goes through 2023 and will surely look better once 2024 is included, but the overall message for this section seems reasonably clear: the post-2021 inflation was a time of solid income growth for low-income workers, middling income growth for median-income workers, and weak income growth for high-income workers.

Relative to the strong across-the-board income gains experienced from 2012 through 2020, however, no income quintile seems to have performed better over the last few years, and multiple income quintiles performed noticeably worse.

Point 2: the median worker had weak real wage growth

As already discussed, from the standpoint of understanding voting patterns, the median change in income seems more important than the change in median incomes.

Thankfully, there is already a good data source out there on median changes in incomes — the AtlantaFed’s wage tracker (which uses linked CPS data). This is the data source used by Afrouzi, Blanco, Drenik, and Hurst’s new working paper, which is an excellent take on how to model labor market dynamics under inflation. Here is the (annualized) cumulative median change in weekly real earnings, by President:8

Once again, the data for Biden only runs through January 2024, and will likely look better as of January 2025, but the conclusion is nonetheless evident: from January 2021 to January 2024, the median worker (as opposed to the median income worker) experienced their slowest rate of real wage increases of the past 30 years, outside of the great recession.

Another way of visualizing this is by just plotting the time-series, an exercise also undertaken in Matt Bruenig’s very good post on this topic:9

As the chart shows, since 1996, April 2021 to June 2022 was the single longest stretch of time the median worker has seen continuously negative YoY changes in real weekly earnings, including the Great Recession! That period exactly matches the stretch of months when YoY PCE inflation crossed 3% up until it reached its peak. The chart also shows that while YoY median growth has turned positive since the start of 2023, it has by no means outpaced its typical level back in 2015-19. Therefore, real earnings have not caught up (to trend) after the period of negative growth they suffered.

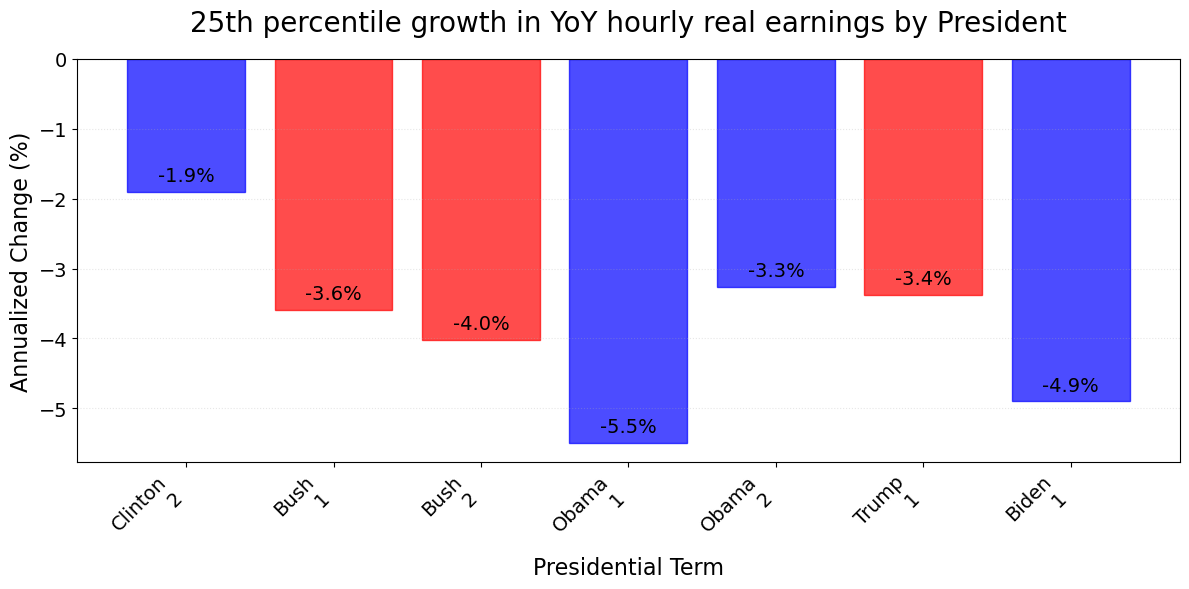

In addition to the median change, the AtlantaFed tracks the 25th and 75th percentile changes — for hourly earnings. Here are the same charts, for those moments of the change in hourly earnings distribution:

These two charts indicate an interesting pattern: the 75th percentile of changes in YoY real hourly earnings during the Biden presidency was actually quite good — workers who did relatively well the last few years saw large increases in real hourly earnings. However, the 25th percentile of changes shows that workers who did relatively poorly did poorly in absolute terms — their cumulative real hourly earnings fell 14%.10

The one important caveat to this data is that it only tracks a given set of workers across two surveys that are twelve months apart. The data does not retain the same workers in the survey across four years — so the median wage change from January 2023 to 2024 is tracking a different set of workers than the median wage change from January 2021 to 2022. As Dube points out, if workers who got (temporarily) laid off during Covid were re-entering the workforce in new, higher-paying jobs, this longitudinally linked data would miss out on that.

It is hard to gauge how distorting of an effect this may be, but one source of support for the above data being closer to “true” than not is the AtlantaFed’s “weighted” version of the data. The weighted series weights by a given month’s demographic, industry, and occupation groups — meaning that if some industries/occupations were disproportionately absorbing new workers at higher wages, as long as those jobs also gave incumbent workers similar raises, the data would reflect that. Comfortingly, the chart looks very similar using the (hourly) weighted data:11

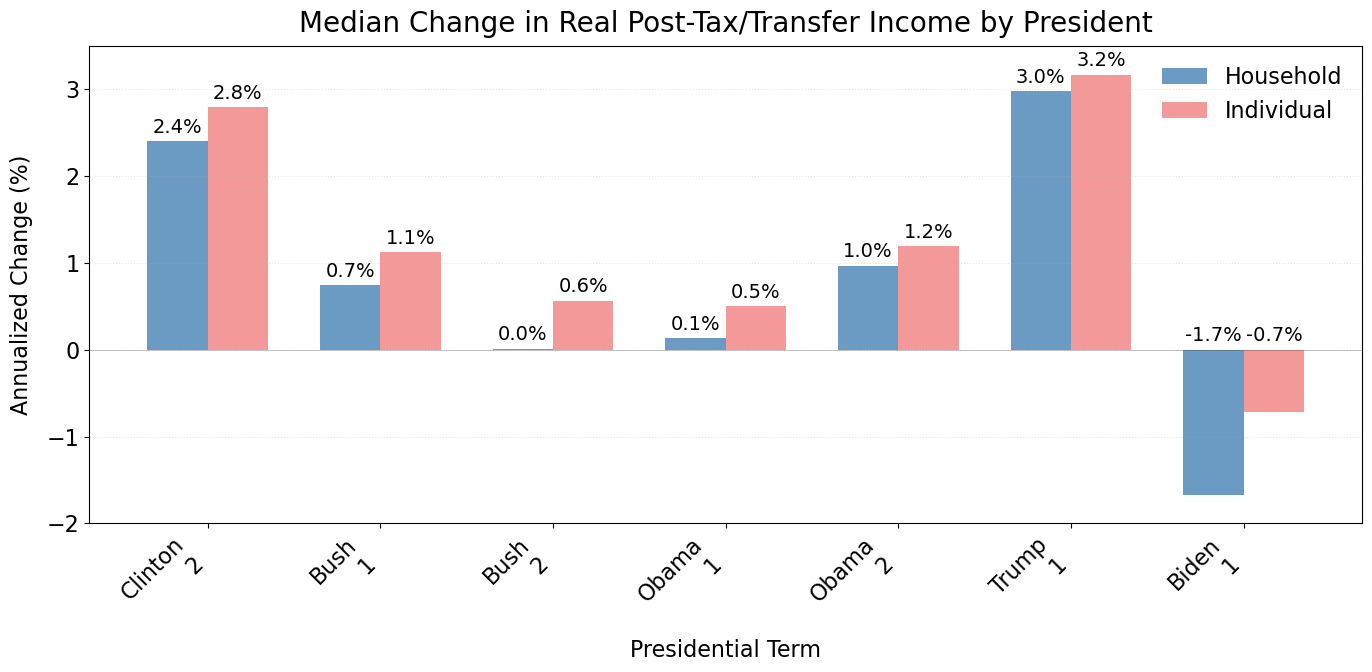

Point 3: Post all taxes and transfers, the median household’s real income collapsed while Biden was in office — due to the timing of the Pandemic stimulus

Much of the debate has centered around the behavior of real wages, rather than real post-tax-and-transfer incomes. Real wages are interesting insofar as they tell us whether inflation was met by corresponding increases in wages or not; yet, if we want to answer the question “did inflation make the median voter poorer,” we want to know about the whole hog: post-tax-and-transfer income.

Suggestive evidence comes from the BEA’s real personal income per capita series, which falls off a cliff in early 2021 after various pandemic relief stimulus packages fade out of the data. But at the risk of repeating myself, from the standpoint of the median voter, per capita income might not be very informative — the median change in incomes is the holy grail we are after.

To answer this question, we return to the CPS ASEC data. The Census uses the ASEC to publish data on growth in median incomes, but not on median growth in incomes. Fortunately, the ASEC samples some of the same individuals and households across consecutive years, and has a variety of variables available to estimate full post-tax-and-transfer incomes.

We can then do the same sort of exercise the AtlantaFed does with wages, this time with incomes, and again cumulating the median year-over-year changes within a Presidency.

Here are the results, with one bar for household incomes and one bar for individual incomes:

Not great!!

Now, I want to be as clear as possible: this is not the fault of the Biden administration, nor is it even really the fault of inflation — the charts from the previous sections better capture the latter. The remarkable growth of real post-tax-and-transfer incomes 2016-2020 followed by their unprecedented decline 2021-24 is primarily due to the timing of the various Pandemic relief checks, which doubly penalize Biden: Trump looks comparatively strong due to the 2020 boost, and Biden’s data is extra weak due to the reference point being the stimulus-fueled high that was 2020.

Here is how things look if we exclude Covid from Trump’s presidency (so the annualized change is January 2017 to January 2020) and “give” Biden a January 2020 start-date:

I think this is an overly generous experiment for understanding voter’s perceptions of their incomes during Biden’s presidential tenure, but even still, the median change in after-tax-and-transfer household income is well below its 2012-19 run-rate.

The table stakes: where I disagree with the optimists

To reiterate where my analysis differs from charts which show strong wage growth for some percentile of the income distribution: I think those charts are misleading for understanding the election because a) they compare wages now versus January 2020, rather than January 2021 b) they focus on changes for a given percentile rather than median changes c) they look at pre-tax hourly earnings rather than weekly, annual, or after-tax earnings.

This figure displays how these different methodological adjustments affect things, one-by-one.

I start with 40th-60th percentile real hourly earnings growth from December 2019 to December 2023, which (almost exactly) replicates Dube’s number in his second chart here. The visual difference between my bar and Dube’s is primarily because mine is annualized (cumulative growth would be 6.3% on my replication).12 The next bar switches to deflating by the PCE, which boosts annualized growth by 0.6pp.

The third bar changes the time period from December 2019-December 2023 to January 2021-January 2024 — causing a 0.7pp fall in annualized growth. The next bar switches from using average growth in 40th-60th percentile hourly earnings to the annualized cumulative median change in hourly earnings (from the AtlantaFed). The next bar uses the CPS ASEC data to look at the annualized cumulative median change in after-tax-and-transfer individual income. The final bar switches from individual to household income.

This final figure shows that the same sort of methodological changes do not drag down annualized growth under Trump’s presidency:

In this figure, from the third bar onwards, to prevent Trump’s post-tax data from looking “too good”, Trump’s data excludes Covid and runs from January 2017 to January 2020. The above chart is my most succinct reason for thinking that inflation did make a meaningful fraction of voters poorer, in a way that likely affected the election.

Many of these points represent a different perspective than Arin Dube on which data points are most relevant for understanding the election, but I want to emphasize that Dube’s work on this topic (along with Autor and McGrew) has been excellent and a boon to my own analysis.

Conclusion

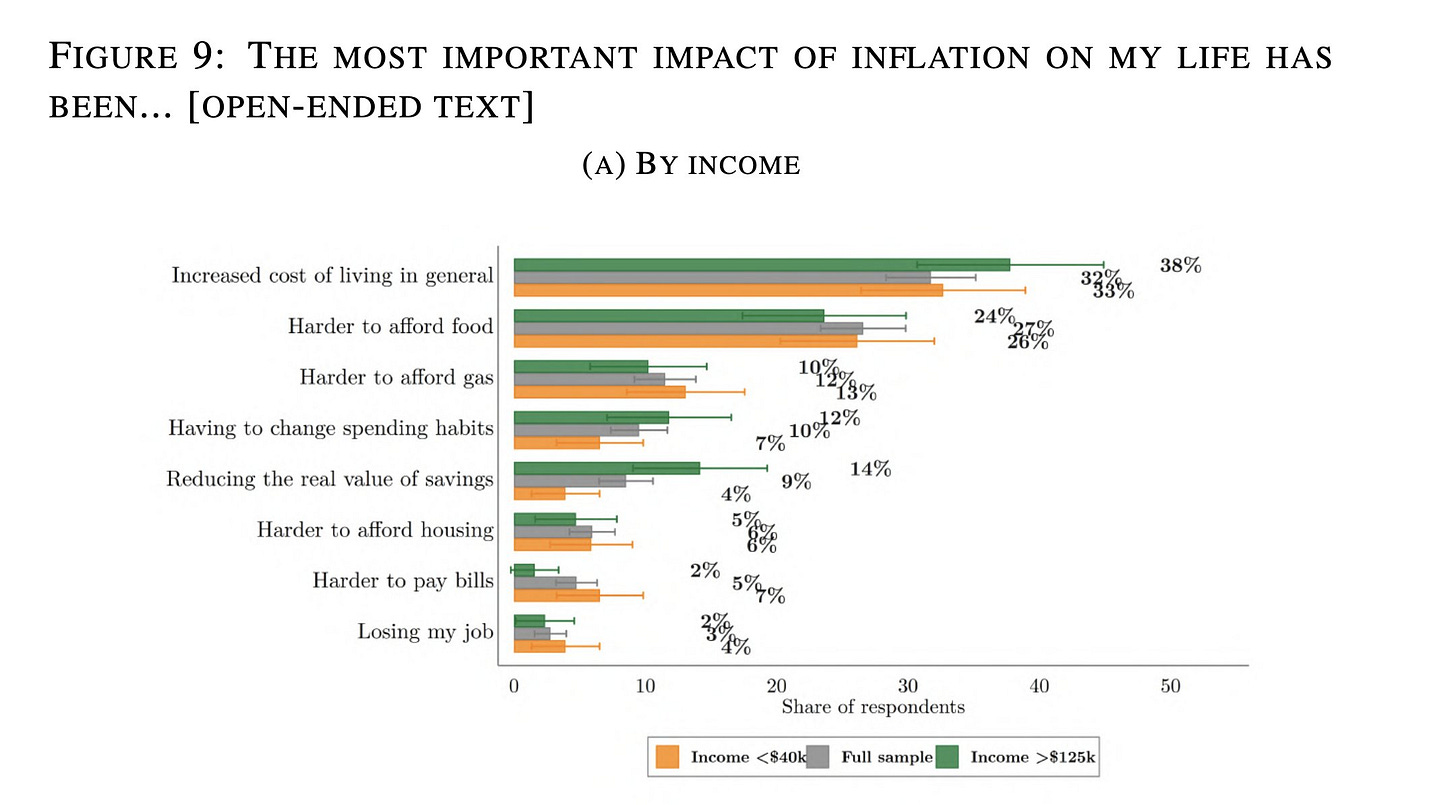

How all of this plays out in the psychology of the voter is something that is hard to say with any confidence, but fun to speculate about. Is it plausible that voters implicitly have the “reference” point of their cash-rich 2020 (and early 2021) and mostly associate the Biden administration with a (historic) deterioration in how much they feel like they’re taking home?

Given that what people say they don’t like about inflation is the decline in their purchasing power, people being aware of this decline in their real take-home pay is more plausible to me than theories which emphasize media bias, the higher costs of financial planning, or the costs of having to negotiate an inflation-raise. The strongest version of the weak real income growth theory relies on people having some degree of economic irrationality13 — over-anchoring to the reference point of 2020 incomes — but given that “reference points” are about as robust an economic bias as we are aware of, it’s a theory that I think has some real bite.

That’s not to say that the other theories just mentioned aren’t part of the story: there is good evidence that people rate their own finances as much better than aggregate economic conditions, supporting the media bias narrative; and there is fascinating survey evidence that people would be willing to pay a lot to avoid having to negotiate an inflation-raise. There is also the awkward fact that which income voters moved towards Trump doesn’t perfectly align with the by-income-percentile patterns identified earlier.

Yet, I think it’s hard to look at the charts from the previous two sections and not think the fact that median growth in incomes was much weaker than it was during the prior two Presidencies is a major part of voter’s discontent.

When I sent an earlier draft of this post to my co-author Basil Halperin, he mentioned that he buys the “menu costs on wage negotiations” story more than me,14 but at the same time, the election made him feel “righteous about the success of the simplest sticky wage model.” He explained as follows:

The Fed allowed high inflation

High inflation + sticky wages = low real wages...

...and low real wages result in low unemployment and high output

Pundits: “the economy is good — low unemployment, high GDP — why don’t the voters understand??”

But low unemployment and high GDP are precisely caused by the low real wages — which is, rationally, what voters care about!

Output is high, and this is BAD — exactly the prediction of the basic model

Back to Zach: add-in a bunch of stimulus checks that households got right before inflation really kicked-off, throwing off household’s “baseline” income, and you have the makings of some unhappy voters. Or at the least, some voters who no longer felt like voting for the Democratic candidate.

Thank you to Basil Halperin and Sam Lazarus for extensive feedback on this draft.

Update (Nov 17 2024): In the wake of writing this post, David Splinter kindly emailed me to let me know about his paper with Jeff Larrimore and Jacob Mortenson which uses a panel of tax data to precisely measure after-tax income for fixed sets of workers over time. Their data only runs 1999-2022 and is not able to be used to calculate median changes, but does make clear the importance of 2020 transfers. Figure 2 in their paper shows that post-tax-and-transfer real incomes for all three of bottom, middle, and top income quintiles peaked in 2020, slightly declined in 2021, and collapsed in 2022.

I also have written a twitter thread with a few thoughts on related issues the piece does not cover.

I found the linked image through Adam Tooze’s Chartbook piece, but the original figure comes from this Bloomberg article.

Assuming that all workers in this toy example can vote.

The first point is that it is not clear what the “right” number to look at is, especially given the mayhem that Covid-19 wreaked on all economic data. I think the best answer is something like the following: for each household unit which includes an eligible voter, take cumulative (real) post-tax-and-transfer income from January 2021 through October 2024, divide by cumulative (real) post-tax-and-transfer income from January 2017 through December 2020, and compare the median growth rate of “across-Presidency average real income” with its historical trend.

But there are some obvious counters to that answer: maybe people have recency bias and it is better to just compare their real income in the year of the election with their real income in the last year of the prior presidency. Maybe individual income is more relevant than household income. Maybe people think about transfers differently from wage income. Etc!

The second issue is that if we want to look at the median growth rate of eligible voter incomes during the Biden presidency, we need a panel of data that tracks the same workers over time. Tax data would do just that, but tax data is not publicly available, and there is no other data source (that I’m aware of) which provides that data through the years 2021-23. The panel study of income dynamics (PSID) is a multi-year linked panel, but the most recent available data is from 2021.

Of the data we do have, the source that best allows us to compare matched individuals over time is the current population survey (CPS), but the issue with the CPS is that matched individuals only appear twice (12 months apart). Therefore, when we compare wages in (say) January 2021 to (say) January 2022, we only capture people who were working in both periods. If people were re-entering the workforce after being fired during Covid, we also want to know how their wages changed relative to their most recent employment stint, but the CPS doesn’t allow us to figure that out. Arin Dube has some more discussion of this issue here.

If we are not comparing matched individuals over time, then we need to adjust for the changing composition of the workforce to be able to identify the median growth rate of income. Depending on how one makes those compositional adjustments, one can come to different conclusions about the behavior of real wages.

UPDATE (Nov 17 2024): David Splinter emailed me to note that you don’t actually need linked-Census data, you just need tax-return data. In his words: “In LMS (2021), we showed that one does not need the Census data for this. Instead, one can link tax units into households (i.e., multiple tax returns and non-filers) by address and replicate the Census household income distribution while also capturing underreported top incomes, tax credits, and using actual income tax liabilities.”

Real hourly wages are constructed as nominal hourly wages in a given month divided by the PCE price index in that month. Nominal hourly wages come from the CPS data, and I have tried to adhere to the data construction procedure used in Autor, Dube, and McGrew exactly (when I try and replicate their figures, I get very similar results, though not 100% identical). The annualized change comes from taking real hourly wages in the last full month of the presidency (i.e. December 2016 for Obama 2nd term), dividing by real hourly wages in first month of the presidency (i.e. January 2013 for Obama 2nd term), and then annualizing the cumulative growth. For Biden, the data only runs through March 2024, and the annualized growth rate takes the shorter sample into account. Trump “pre-Covid only” runs through February 2020.

The CPS data plotted in the previous chart (and used in Autor, Dube, and McGrew) is weighted to maintain a representative population of workers in each month, but is not held compositionally fixed across months.

Technically, he is constructing triangle-weighted averages where “for example, the 25th percentile is [a] weighted average of the 21st through 29th percentiles, with weights of 1/25, 2/25, etc.” Tedeschi’s data is quarterly, so presidential cumulative growth in real wages is constructed from Q1 of the first year of a President’s term to Q1 of the first-year of the next Presidential term (i.e. 1981 Q1 to 1985 Q1 for Reagan’s first term). The Biden data runs through 2024 Q1 and is annualized accordingly.

The same cannot be said for earnings of full-time year-round workers, where there is a a noticeable 2020 bump in median earnings alongside a sharp fall in the number of workers who count as full-time and year-round. Compositional dangers are clearly afoot!

This is back to using the PCE as the deflator. I use the AtlantaFed’s three-month moving average of the median weekly earnings change, from January when a President enters office to January after they exit office, in order to use four separate (non-overlapping) “median twelve-month changes.” The results look very similar if you use the AtlantaFed’s hourly wage series instead of weekly earnings.

I have again deflated by the PCE while Bruenig deflates by the CPI.

-14% is a -4.9% annualized change compounded over three years.

The weighted data is based on hourly earnings not weekly earnings.

Cumulative growth would be 6.3% on my replication, while it looks like it would be a touch higher in Dube’s data. I have done my best to replicate Dube’s methodology as closely as possible, but I haven’t been able to perfectly do so. Here is Dube’s figure:

And here is my replication:

My results are very close, but they don’t line up exactly — particularly for growth in bottom fifth incomes. Given how close my replication is, I don’t believe the residual error in my replication is driving my results, but if someone has evidence to the contrary, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Though just having habit utility functions would get you pretty far.

The main reason I don’t put too much weight on the “wage negotiation cost” story (of Guerreiro, Hazell, Lian, and Patterson) is that if people do perceive such negotiations as extremely costly, I would expect people to mention those costs when asked about the biggest impacts of inflation on their lives. Yet, in Stefanie Stantcheva’s open-ended survey question on “the most important impact of inflation on my life,” no one mentions wage negotiation costs:

The author’s have a different perspective on Stantcheva’s evidence, which they lay out in this twitter exchange. I do think the author’s survey evidence that people would be willing to give up a significant amount of wages to avoid having to negotiate a raise is compelling (and very interesting!), however, I don’t think their survey is well suited to compare the costs of different aspects of inflation. Stantcheva’s evidence seems to speak more directly to the comparative costs of different channels.

Why is the pandemic stimulus "less the fault of Biden" than other things? There were two stimuluses. One passed under Trump, which was arguably defensible, and one completely unnecessarily stimulus once Biden took office. That was passed just to show he was "doing something" about the pandemic too. If anything, this analysis shows Biden deserves a lot of blame.

Great post. Thanks! I suppose one further consideration is the distribution of inflation by income. My impression is that there isn't much data on the inflation distribution. But it is plausible that different income percentiles are experiencing different inflation rates due to the different mix of goods and services consumed.